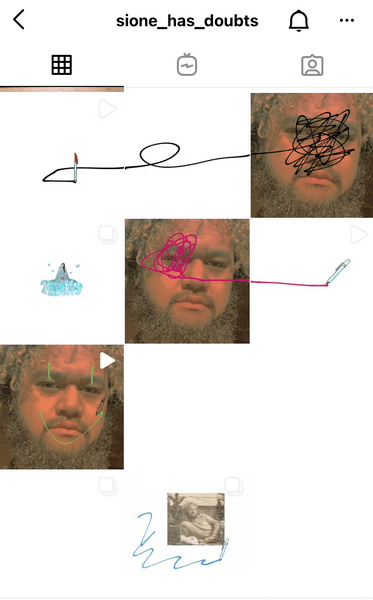

The first image in the Instagram account @sione_has_doubts is a drawing. It’s rendered with brushes and pens in an iPad painter’s app and presents a self-portrait of the artist, Sione Tuívailala Monū, candidly glancing beyond the frame. Monū holds a cigarette in one hand and could be picking an eyelash off their cheek with the other. Amusing and a little melodramatic, it milks the cliché of the nonchalant, intellectual artist. To me, it stands for the digital avatars we inhabit, which most of us assume as second-nature, gliding through slippery, amorphous worlds. This increasingly malleable condition of the self has become a medium for artists. In the first sense of the word, ‘medium’, the digital avatar is a material, a raw substance which can be co-opted, stretched and transformed to convey the particular ideas of the artist. In the second sense of the word it is also an interface, a visual and shared language between experiences, physical bodies and ethereal bodies.

@sione_has_doubts is like any Instagram account. Amassing photographs, videos and text, it acts as the prism through which we view Monū’s life. Monū is the ‘main character’—they imagine themselves as the lead part in the story that is their life, and parody how this individuality complex is apparently exacerbated by social media. In an interview with their friend and collaborator Manuha’apai Vaeatangitau for The Art Paper, Monū attributes this syndrome to ‘[living] vicariously through’ a wide range of cinema from a young age, which, in turn, has ‘influenced not only [their] eventual video practice but how [they] experience life.’

In some posts, their iPhone is set up at a distance, and the image slowly pans across the unwitting protagonist in distant, cinematic form. The camera peeps through the blades of a lawn in summer as Mōnu smokes and contemplates the clouds, or watches them as they take selfies with the flash on under a full-moon. Friends and family often feature as collaborators or blasé extras. Monū’s captions are impulsive, philosophical or recommend things to read, watch or listen to. Followers leave celebratory and encouraging comments. Despite existing within an Instagram format, these techniques have come to shape a distinctive filmic vernacular, as Monū says ‘I think if I just keep making work that talks to my experiences of the world real, and imagined, there will be a cinematic language naturally birthed from it.’ Monū proposes that Instagram can be considered as a descendant of cinema, and can take on its affective and critical modes.

Monū takes more steps than the average Instagrammer to refine our viewing experience. Each new post is framed by a flurry of blank white squares, so that when you view the profile as a whole—imagine taking a step back—it’s as if the post is mounted on a virtual white wall. Monū also uses these white squares to form larger compositions of images, emojis and scribbles, which flutter across the profile with installation-art finesse. It’s clear that, though tongue-in-cheek, it all wants to be looked at like art.

Artists have used social media as their stage before; some of the most famous including the dead-pan Tumblr star Molly Soda, who in 2012 read out every piece of fan mail on her page for ten hours,[1] and the Instagram influencer Amalia Ulman, who horrified thousands of followers in 2014 after revealing that her whole personality was fake.[2] However, given the fact that 85 percent of the influencer population are white women, Soda and Ulman succumb to the odds as much as they try to offer a dissociated critique. Monū doesn’t seem too phased by the eccentricities of internet celebrity—in fact they’d rather embrace it. With an expansive view of the world, their expression focuses on their experiences of living in diaspora and identifying within their community as a leitī—a Tongan word meaning the third gender.[3]

Instagram, like any social media platform, swings between the micro of individual lives and the macro of a world at our fingertips. Incidentally, this dynamic is illuminating for identities which span oceans. As Lana Lopesi states in her totemic text, False Divides: ‘Social media makes visible the multiple and multi-layered ways of being from Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa. This includes the clashing perceptions of one’s own culture, as influenced by factors such as diaspora, class and generation.’[4] To build on Lopesi’s point, social media’s very structure contributes to the ‘layeredness’ of how we express ourselves and understand each other in the digital age. The writer and critic Nora K. Khan has described social media as a technology of augmented reality, which she defines as ‘flexible digital practices…that layer media, including images, writing, chat programs, and virtual objects, atop one’s existing visual environment’.[5] Monū’s ‘layered play’ portrays lived experiences forged by the forces of colonisation, globalisation and the immersive effects of the internet. As a voice in diaspora, they are empowered by the customizable forms of communication which we live amongst, which ‘demand attention, a sharpened quality of seeing, and an active balance between multiple competing modes of vision’.[6]

@sione_has_doubts ran from March to November 2019, when they made a story announcing its end, because ‘finna experience life fully irl now!’ It echoed the jitters we all get when we’re confronted by our screen-time reports.

‘finna experience life fully irl now!’

@sione_has_doubts

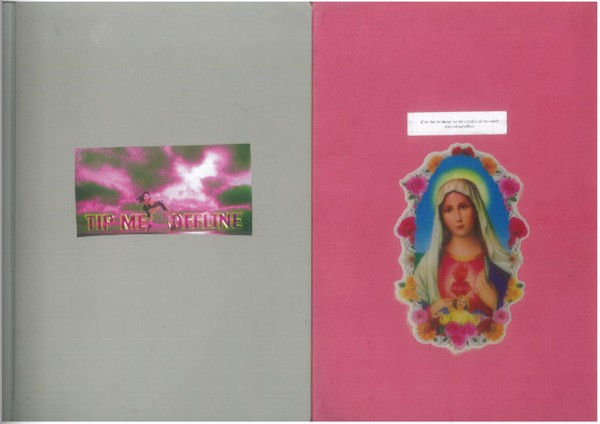

Ming Ranginui’s Patreon account deliriously falls down those internet rabbit holes we try to avoid. Titled ‘the pillow princess of fine arts’, her account and its contents were created for a university assessment—her assessors were forced to become patrons with the options of paying two, five or seven dollars to mark her work. Her name, ‘the pillow princess of fine arts’, paints a picture of her lying before her laptop, feet in the air, in an Egyptian-cotton studio.

Like Monū’s, Ranginui’s account is a stream-of-consciousness internet confessional, where writing, digital drawings and videos appear in no apparent order. A page-by-page scan of Ranginui’s workbook reads like a manifesto in a chaotic teen diary (the kind with the tiny key and lock). In it, she’s pasted screenshots, tested paint colours, and annotated images of her work. She’s scrawled her feelings about all the realities she faces as an artist, from spirituality to ethics to financial stability to ‘beef with the institution’. It’s purposefully indigestible—she resists the expectation to explain herself. As she says, ‘It’s a new year, new medium…the medium is me’.

One of the most fascinating elements of her Patreon is the fact that nearly all the work was commissioned through various internet platforms. In the video, The Process, she paid freelancers on Fiverr.com to help her create the work. First, she gave a poet the brief to write about the metamorphosis of a caterpillar, which she then commissioned voice actors to read in the voice they specialise in (‘anime’ and ‘deep American male’ in this case) before finally commissioning a designer to produce the visual content to accompany this audio. A cosplay girl in butterfly face-paint and wings cuts in and out of the video, bouncing awkwardly. The Process is a caterpillar’s disorienting monologue preparing to transform into a butterfly. ‘The process’ says a squeaking, earnest voice, ‘I trust the process…The pressure, pain and stress is all part of the process.’ The message parallels the pressures to succeed within a creative industry like fine arts. Another Fiverr collaboration, Believe in yourself, presents three bikini’d women washing a car with the title of the work emblazoned on its side. They look like they’re in suburban LA. It’s a bizarre package offered by a Fiverr freelancer: ‘I will display your logo on a sexy car wash video’[7] which Ranginui revels in—incorporating a sparkling life motto in the furthest thing from a self-help book. It betrays the gig’s own extravagance. The measly $7.42 fee for such a laborious performance makes money seem completely trivial, it’s even funny. Her Fiverr film’s buzz—hiveminds composed by far-flung strangers.

Fiverr is an online marketplace where individuals from all over the world sell their skills—including logo-design, photo-editing, web development, personalised erotica, rent-a-text-friend, or a crash course on how to telepathically communicate with your pet. It oils the gig economy, but also exhibits the quirks of human nature which flourish in the pits of the internet. This atomisation of the creative economy has caused opportunities to explode in good ways and bad. You can finally make some money from that arts degree, but you are also but a minuscule drop in the ocean that is your competition. Platforms such as Fiverr, Craigslist and Patreon lay bare the entrepreneurial demands of a creative career. ‘Creator’ is the buzzword, describing those who make money off their creative skills through the internet, and encompasses everyone from an influencer to an oil painter.[8] It gilds the ever-present yet constantly evolving question for artists—how to build an audience.

‘creating self-help and spiritual guidance.’

Ming Ranginui

The sales pitch of Ranginui’s Patreon account is ‘creating self-help and spiritual guidance.’ It becomes evident, however, that this pitch is sarcastic—and that such new age, glittery self-belief tactics shrivel within the hyper-capitalist systems that they’re up against. Ranginui’s work bares these realities by playing into the structures that shape them, while mockingly offering her pseudo-guidance as a way out of those same structures (paid, of course).

According to the writer William Deresiewicz, who recently proclaimed ‘the death of the artist’ in our late-capitalist reality, being a successful creative today ‘means being willing to be personal, even intimate, with strangers…You sell your work today by selling your story, your personality—by selling, in essence, yourself.’[9] While the tone is desperate, many of us, especially those of a certain generation, already brand ourselves subconsciously. What we present for others to see, especially within digital space, is informed by what we think success looks like.

The offbeat nature of Ranginui’s collaborations are the subject of her work as much as their unexpectedly poetic results. She experiments with the potential of this online industry by giving over the creative freedom to others, and by making something that goes beyond the dull, ad-hoc commercialism which her collaborators might represent. At the same time, her intentions aren’t actually to be disruptive. She works from within these frameworks to expose their absurdity rather than dismantle them. More importantly, she protects her own worth, making a conscious decision that you’ve still got to pay to play—there’s no way you’ll find this work by Ranginui free to view on a platform like YouTube or Instagram.

*

Machinima is one of the earliest examples of repurposing pre-existing digital technologies for creative ends. It involves using video games to produce cinematic productions, and early films made by gamer circles from the mid-1990s paved the way for what was possible within video game technology. The art world started to catch up in 2007, when Cao Fei created RMB City in the game Second Life. Fei offered a new forum for world-building, from urban planning to community spaces, at a time when virtual reality technology still held its utopian promises.

Connor Fitzgerald’s explorations with video games are distinctly alone in the dreamscape. This body of work, made in 2019, traverses hours spent on Skyrim, The Last of Us, Red Dead Redemption I, Dark Souls, Grand Theft Auto 5, The Sims 3, as well as Second Life, and more.

babixboi and x~Angel~x take different forms from game to game

Fitzgerald’s avatars are ‘babixboi’, which coincided with their Instagram alter-ego at the time, and later ‘x~Angel~x’, a name they had recently given themself. babixboi and x~Angel~x take different forms from game to game, and at times we watch Fitzgerald contemplate and personalise their features—hair, clothes, eye-colour, and gender. The connotations of these features become more and more abstract as we flit between the various historical, mystical and supernatural worlds of the games.

The journeys which the avatars take are analogous to automatic drawing, in the sense that Fitzgerald created their images involuntarily via the tools and toggles of the medium. In some works, it’s clear that Fitzgerald is intent on feeling their way through the quality of this embodiment. In dancin alone… a high-heeled, smokey-eyed babixboi with a dragon back tattoo and tousled bob dances alone on a desert island in Second Life. The ‘no set objective’ of Second Life, when it was created, was to simply live in the game, which included socialising with the other players, working a nine-to-five and taking vacations—activities Fitzgerald disregards in this work. The image clunkily zooms in and out from the dancing avatar, and we hear Fitzgerald’s intermittent mouse clicks amid the melancholic piano music.

In another work, i really am alone arent i…, babixboi is still in Second Life, but is this time found in an abandoned ruin with snow drifting through the ceiling. She gets up and moves through an empty apocalyptic landscape, at one point flying while observing the bolts of lightning flashing below her and the grey hills materialising out of fog. For long periods in these video works, Fitzgerald pays sustained attention to the surroundings of the avatar—from the tiled floor of a subterranean bunker in Second Life, to the water rapids, treetops and rippling clouds in Skyrim. They capture sudden, beautiful moments that disappear as quickly as they are upon us—like a flash of evening sun across a grassy pasture in Red Dead Redemption I, or a butterfly passing by the screen in Skyrim.

Fitzgerald has said that when they first made these videos they felt a deep discomfort towards some of them, including those made in Second Life—that in the moment it felt appropriative and even misogynistic. Years on, they see that these videos were really an unconscious gesture towards coming to terms with their trans-femininity. ‘It’s an interesting thing to reflect on’, they say, ‘that this avatar can come first, without you even knowing what it means’.[10] By traversing these sublime geographies, Fitzgerald produces gentle meditations on how consciousness, embodiment and nonphysical identity manifests within our technological present.

*

The ‘avatar artist’ LaTurbo Avedon, whose use of video games is a key influence on Connor Fitzgerald’s work, has summed up the shift occurring towards understanding digital practices. ‘There was a time where places like these seemed truly separate—the idea of digital dualism seemed to be real—but today places like these seem much more familiar and tangible, and not so different than the waking physical world. If anything, as users are augmenting their perception and interfacing with their devices, physical environments are becoming more like virtual ones.’[11]

Today, our sense of space and identity is perpetually mediated by our digital universe. The works in this essay anchor the artists in the ephemeral spaces which shape their physical ones. Connor Fitzgerald’s essayist films about the connections between the environment and our physical embodiment now manifest in hypnotically real settings. Ming Ranginui’s sculptural practice draws together disparate symbolisms and mediums with the same razor-sharp perceptiveness. Sione Tuívailala Monū’s broad and busy artist practice hinges off their Instagram account, where early experiments with video, mink blankets and plastic flowers first appear in an open-book process. By co-opting the arguably dull, graceless and restricted aesthetics of their mediums, the artists dramatise how we interact with digitality, and how it has claimed an inherent part of us.

Above all, Monū, Ranginui and Fitzgerald demonstrate the boundless connective potential of these immaterial extensions of our being. They draw us in, shrinking space and difference, and offer resourceful and unexpected ways of seeing. Their works abate the feelings of submergence that can often accompany our individual quests to make sense of the world today, especially within digital space.

In another work for her Patreon, pearlz, Ming Ranginui ordered a custom ‘pearl reveal’ from Minnesota-based company ‘The Pearl Dude’. For $25 USD a pop, you can tune in to watch the shucking of an Akoya oyster and live the thrill of seeing it emerge into the light for the first time. You don’t know what colour it will be, and according to The Pearl Dude, ‘each colour has [a] unique meaning: white (health), pink (love), purple (wisdom), black (success)’.[12] The voice belonging to the gloved hands announces Ranginui’s name, then two oysters are swiftly opened and stabbed and a tiny pearl rolls out of each. The voice describes their colours and measures them before laying them on a bed of shimmering white sand—one is a pinkish-purple, the other a light-pink. ‘Pretty…’ says the voice, ‘congratulations to Ming.’ It’s whimsical, but also magical and hopeful. Despite being so remote from the messy bedroom you might watch it in, it feels close.

Moya Lawson is a curator and writer based in Pōneke, Te Whanganui-a-tara. She has been a facilitator at play_station gallery and studio space since January 2019. She has also held various roles at City Gallery Te Whare Toi and was a Venice Biennale Exhibition Attendant in 2019.

Footnotes:

[1] Molly Soda, ‘INBOX FULL’, YouTube, 2012, accessed 24/09/2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XdfIXkwvU1Y

[2] Amalia Ulman, ‘Amalia Ulman: Excellences and Perfections’, Rhizome, 2016, accessed 24/09/2021, https://webenact.rhizome.org/excellences-and-perfections/

[3] Sione Tuívailala Monū and Manuha’apai Vaeatangitau, ‘Sione Tuívailala Monū, Leīti’, The Art Paper New Zealand, 2021, accessed 24/09/2021, https://www.the-art-paper.com/sione-tuivailala-monu-leiti/

[4] Lana Lopesi, False Divides (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2019), 65

[5] Nora N. Khan, ‘Light Play: Twisting Reality and Deepening Narrative through Augmentation’, Mousse Magazine, 2017, accessed 24/09/2021, https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/nora-n-khan-augmentation-reality-2017/

[6] Ibid.

[7] designlevi, ‘I will display your logo on a sexy car wash video’, Fiverr, accessed 24/09/21, https://www.fiverr.com/designlevi/display-your-logo-on-a-sexy-car-wash-video

[8] Sophie Bishop, ‘Name of the Game: “Creator” and “influencer” aren’t different jobs. Who does it serve to pretend they are?’, Real Life Magazine, 2021, accessed 24/09/21, https://reallifemag.com/name-of-the-game/

[9] William Deresiewicz quoted in ‘How can we pay for creativity in the digital age?’ by Hua Hsu, The New Yorker, 2020, accessed 24/09/2021, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/09/14/how-can-we-pay-for-creativity-in-the-digital-age

[10] Connor Fitzgerald, ‘CIRCUIT Cast Episode 95: Connor Fitzgerald and Xi Li’, Circuit Artist Film and Video Aotearoa New Zealand, 2020, accessed 24/09/2021, https://www.circuit.org.nz/blog/circuit-cast-episode-95-connor-fitzgerald-and-xi-li

[11] La Turbo Avedon, ‘LaTurbo Avedon on identity and immateriality’, The Creative Independent, 2018, accessed 24/09/2021, https://thecreativeindependent.com/people/laturbo-avedon-on-identity-and-immateriality/

[12] The Pearl Dude, ‘BOGO Oysters’, The Pearl Dude TM, accessed 24/09/2021, https://thepearldude.com/collections/oysters/products/oysters