In the space between the publication of The Aotearoa Digital Arts Reader in 2008 and the writing of this text, significant global developments in the marketability of born-digital art have taken place. Unlike earlier forms of dematerialised art production such as Conceptual Art, digital art has largely managed to avoid institutional recuperation through its resistance to dominant market values: scarcity and authenticity, transfer of ownership, and permanence. The drawback of this independence has been digital artists’ inability to make a living directly from their creative output, relying on alternative sources of funding to maintain their practice (at best). Experiments in the financialisation of internet-based art began as early as 1993, when the sale of Peter Halley’s digital image Superdream Mutation was facilitated via internet platform THE THING. Unique editions of the algorithm-driven work Every Icon (1997) by John Simon Jr. followed four years later, another anomaly given the anti-art market sentiments shared by many early net.artists.

The internet today is not the optimistic, exchange-based culture that net.art emerged from during the early 1990s. Capital has crept into even the most inane corners of the internet since the dot com boom and bust, consuming social interactions and expelling them as marketing data. Creative works from explicit selfies to independent podcasts have increasingly shifted behind subscription-based paywalls (OnlyFans, Patreon), producing new attitudes towards the value of digital ephemera. In the last few years, cryptocurrency technology has given rise to NFTs or Non-Fungible Tokens, a new online infrastructure for the transfer of ownership title. The newness of this technology has engendered numerous hot-takes and hyperbolic headlines, but few have explored the historic position or local relevance of NFTs in depth.

NFTs and Artificial Scarcity.

NFTs can be used to trade anything unique with cryptocurrency, from a physical painting to collectible sports cards. Their power, however, lies in the novel ability to create artificial scarcity for digital files.

NFT’s resolve the lack of scarcity that traditionally renders digital files unsaleable (by nature of their infinite reproducibility). This is achieved by attaching a genuinely unique – or non-fungible – token to the “original” artwork file, in theory the first version of the file ever created by the artist themselves.

This unique token, which is essentially an encrypted piece of information, and its attendant digital “original”, is then embedded to a cryptocurrency blockchain as an NFT. Once registered, it can be transferred to another user of the chain by exchanging cryptocurrency.

A novel technology which has emerged with the rise of cryptocurrency trading is known as the blockchain: the “building blocks” or decentralised data structure supporting cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum, and therefore also NFTs. Amongst the handful of independent local artists I have surveyed, the current position on NFTs involves excitement for the conversations surrounding their development coupled with a hesitancy to gamble on the initial registration fees. This general hesitance seems to be due to the technology’s newness and opacity (read: lack of anecdotal evidence that work will actually sell as an NFT). In some cases, further investigation has shed light on the excessive energy consumption required to register or “mint” NFTs and keep its respective blockchain running.[1] And naturally, a healthy dose of scepticism also exists towards the uneasy marriage of independent art makers and Silicon Valley’s idea of an empowered art market.

The reason we should be paying attention to the phenomenon of NFTs is not due to its virality or because its environmental impact is negligible (it isn’t), rather because of its place in the lineage of art historical disruption and transformation. If this technology were to really take-off—to become an accessible alternative to the current market system—blockchain applications could significantly expand the horizons for financial recognition in a shifting and slippery internet culture. That is, if it isn’t first captured by the ‘recentralising forces’ of platform capitalism, wherein a small handful of companies develop a monopoly over the market by providing ease of access to users.[2]

Blockchain and the art world

What has been fascinating to observe in this space is the intersection of NFT artists’ and free-market technologists’ counter-cultural ideals–distinct from the early days of digital culture, when net.artists largely opposed the ‘Californian Ideology’: a vision of the internet as a frontier of infinite profit where digital citizens would transcend the grasp of the state.[3] While creatives in particular tend to hold fast to the internet as a last bastion of free sharing and expression, current material conditions have seen a new community of creators embrace the importation of more-or-less traditional ownership models in the form of NFT platforms—only these models are being packaged and sold as a radical alternative to the existing gallery system.

The Venn diagram where digital artists and NFT platform developers meet is most evident in the overlapping rhetoric touting a ‘crypto revolution’ capable of irrevocably disrupting the traditional market and redistributing agency to the hands of creators.[4] Key to this unlikely alliance is the soft anarchy of the blockchain, where no central authority (such as a government, bank, or legal system) is required to regulate transactions.[5] This feature is what first caught the attention of the art world; the transfer of a work’s ownership, its provenance, can be irrefutably recorded for the first time in history through the transparent and ostensibly secure architecture of the blockchain.

Although the recent media craze surrounding NFT sales has brought this evolving technological infrastructure into mainstream consciousness, it remains to be seen whether these developments can genuinely disrupt the art market or alter the material realities of marginal creators. After all, the emergence of the internet prior to the establishment of the World Wide Web brought with it similarly utopian speculation–much of the current ideology surrounding the potential of blockchain echoes the enthusiasm for a decentralised network amongst early net.artists, and Conceptual artists’ hopes to undermine the object-centric art market before that.

In the 1990s, proponents of open-source software believed in the democratising potential of information exchange, a belief probed by artistic experiments that put the liberating potential of network culture to the test. At a time when the promises of a democratic internet were at odds with its co-optation by market forces, artist Heath Bunting (a champion of democratic and open systems) paired with Natalie Bookchin to create Criticism Curator Commodity Collector Disinformation in 1999. The webpage and its contents–a guide to counterfeiting net.art criticism, press releases and sales–was an attempt to undermine the institutionalisation and commodification of digital art.[6] One of the site’s subheaders stated: ‘Counterfeits do not destroy the original objects, but only their symbolic value, hence the market’.[7]

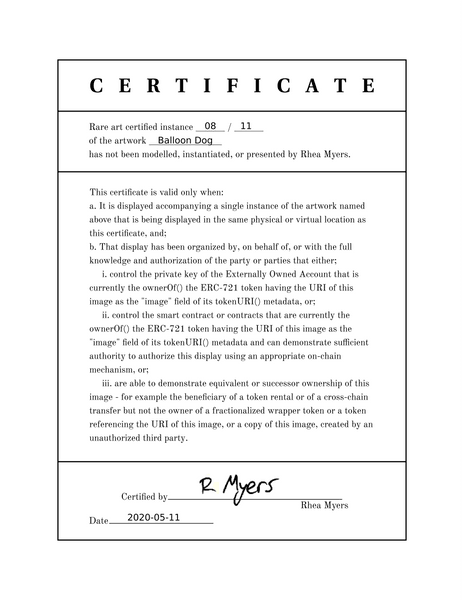

Then, as now, artists were at the forefront of a culture examining the possibilities of a nascent digital future, capable of drawing out the complexities and potential hypocrisies of its early implementation. Rhea Myers’ NFT work Certificate of Inauthenticity (2020) for example subverts the seminal work of Conceptual artist Sol Le Witt, questioning whether notions of authorship and legitimacy are relevant in an online space of unregulated appropriation and reproduction. It’s no coincidence that this work echoes Olia Lialina’s Agatha Appears (1997), or Location=YES (1999), two net projects that identified the unique URL or exclusive domain of a work as the only indices of originality or legitimate authorship in an environment where everything is otherwise replicable and manipulable.[8] Lialina’s works hold relevance to this day: despite the promises of authenticity across NFT platforms, artists are finding their work uploaded to the blockchain without their knowledge or approval.

Some other themes of early net.art have carried over to the NFT sphere—generative and evolutionary art (only in the form of breedable CryptoKitties), appropriation of low-fi and mass media aesthetics, irony—though conceptually engaging NFTs are still rare. Virtual marketplaces are designed for accessible, saleable digital objects that investors can easily collect, discouraging more experimental works that involve aesthetics dispersed over multiple webpages. Some would argue that removing barriers of entry—the democratising feature that is key to the popularisation of NFT platforms—has resulted in the proliferation of empty and self-referential aesthetics.

Accessibility and local uptake

The need for a middle-man such as a dealer gallerist or a recognised institution is negligible for NFT artists, enabling emerging creatives to upload content directly and transact ownership through relatively user-friendly market platforms. While these marketplaces streamline the process, creating an NFT remains relatively inaccessible; registering or minting an NFT requires an artist to purchase cryptocurrency in order to pay gas fees—similar to handling fees, these cover the energy consumption involved in the minting process. Because these fees fluctuate between and within marketplaces, most newcomers will fall into a circular deep-dive of research to establish whether the fees actually pay off, or whether NFTs and their associated cryptocurrency are little more than a sophisticated Ponzi scheme for the average user. Of the artists I spoke to, four had purchased Ether coins to register a work to the popular Ethereum chain, and all have yet to see a return on their initial investment.

Critics have pointed out that the noteworthy NFT sales tend to favour celebrities and artists with an established following, mirroring the traditional market logic which blockchain supposedly subverts.[9] An Aotearoa-based NFT ‘masterwork’ platform set to launch this year, Glorious, has demonstrated this tendency with a line-up boasting some of the country’s most successful dealer-represented artists of the day: Karl Maughan, Dick Frizzell and Lisa Reihana have been announced as collaborators in the same breath as retired rugby star Dan Carter.[10] While this criticism certainly isn’t unfounded—the rhetoric of inclusion and accessibility is frequently empty—there are significant pockets of previously marginalised or untrained artists who are seeing recognition and profit through this new technology.

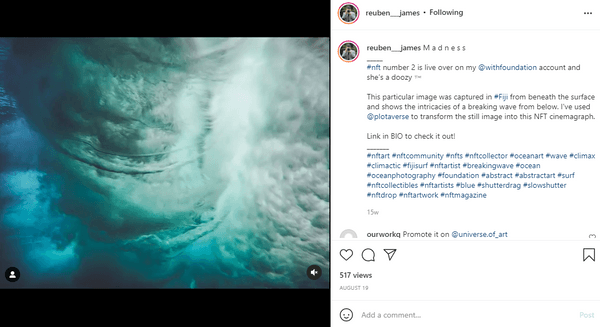

Without wanting to fall into the trope of Aotearoa as a remote archipelago yearning for acceptance within global art centres, NFT platforms do present another way for creators to reach international audiences without the prerequisite local recognition. A growing number of indigenous digital artists working outside mainstream art institutions can be found on NFT marketplaces, such as Allen Onesian on the platform MakersPlace, photographer Reuben James (Ngāti Pāhauwera), and Thomas Clark of Matakiore Ta Moko / Kirituhi Studio. Clark spent months learning about the technology before minting one of his digital images and, in contrast to the traditional art world, has found the NFT community on social media to be very giving.[11] The intersection of new media and Māori art practices is not without precedent either: from Lisa Reihana’s early video art to Kereama Taepa’s fusion of 3-D printing and Virtual Reality with whakairo (carving), contemporary Māori artists have been at the forefront of technological innovation in the arts, contextualising each new development within a te ao Māori worldview.[12]

In order to gauge how accessible NFT technology is to local artists, I asked a number of creatives in Aotearoa to share their thoughts on the blockchain. Motoko Kikkawa, an Ōtepoti-based artist and experimental musician who primarily creates intricate drawings on paper, has created an NFT by scanning a drawing and editing it with Photoshop.[13] Citing the limitations of physical art making and the wasteful use of materials experienced at art school, NFTs present an alternative where an ‘imaginary kingdom’ can be built for Kikkawa; a potential future where a more sustainable direction for immaterial art making is possible.[14] This optimism seems to be in keeping with a general trend of artists who have been following developments in blockchain before the NFT hype, which would suggest that the possibilities of this space are still undetermined. The future applications of the technology are not yet set in stone, evidenced by the number of competing NFT platforms currently exploring more energy efficient mechanisms for registering artworks (known as “Proof of Stake” minting processes). Founder of Babysitter online magazine and digital artist Max Mollison is interested in getting involved but is finding the process of minting an NFT to be less than accessible.[15] Another popular stance is summed up by established painter Evan Woodruffe: ‘I’ve yet to see evidence that they’re anything but a pyramid scheme run on bad energy. They use a disproportionate amount of energy, largely derived from fossil fuels, merely to prove ownership of a digital image, which they cannot do’.[16] These examples echo the sentiments of a number of Aotearoa-based artists who have expressed similar views in panel discussions and candid conversations, providing a cross-section of the current approach to NFTs in the local art scene.

Intellectual Property

Transferring ownership rights through this technology doesn’t shift the intellectual property rights of the artist–these remain with the original creator, maintained through a “smart contract” embedded in the blockchain transaction.[17] It also doesn’t mean the digital object can’t be reproduced or used elsewhere by individuals who haven’t paid to own the artwork; creating an NFT isn’t about inhibiting reproducibility or appropriation (though the conditions of a smart contract may technically state otherwise). While artists have better recourse to resale rights when an artwork is “flipped” or promptly resold on the same blockchain it was purchased through–which is one way of upholding their intellectual property rights–artistic authorship is arguably no less stable in this new arena.

Smart contracts can license the new owner of the work to share or utilise the file in certain ways, only this system has little to no bearing on the actions of other internet users. In 2016, artist and writer Hito Steyerl characterised early blockchain applications with a biting critique: ‘media art, like Bitcoin, tries to manage the contradictions of digital scarcity by limiting the ilimitable.’[18] Unlike proto-NFT platforms such as Monegraph and Ascribe, which were built to protect digital IP using blockchain, the largely unregulated copyright status of NFTs resolves this tension between traditional transfer of ownership and the nature of the internet as an untameable site of appropriation. By issuing an encrypted token–the only truly scarce asset here–along with each transacted artwork, the creative content is still free to be disseminated widely by the author and other individuals. This way artists are able to promote their work without the need to hide it behind a paywall, similar to the way in which a painting sold to a public collection remains in public view.

The uptake of NFTs is most fascinating in that they create only a semantic “original” of a digital file. Digital files can be replicated perfectly by anyone, with absolutely no difference between the integrity of different versions. What makes a file “original” is then partly comprised of buy-in to the legitimacy and force of the blockchain, and partly the encrypted smart contract that bestows the related file with authentic-original status. To weaken the strength of this concept further is the reality that some of the highest NFT sales have not included the file itself within the blockchain transaction (as this can be technologically impractical), but rather a gateway such as a URL that leads to the so-called original work. Gateways and their hosting platforms are, like all things digital, destined to become obsolete.

The legitimacy separating an original file from its many identical reproductions would seem to depend on a critical mass recognising the market platform’s status–which, surprisingly, there has been to date–and thus you have artificial scarcity. ‘Image anarchism’, or the rampant reproduction of uncredited original works which boomed in the golden age of Tumblr, is accepted as a given of the internet, even though it would seem to undermine the entire NFT project.[19] Instead, this embrace of the internet’s resistance to intellectual property has carved out a niche for the NFT market, a place where you can have your cake and reproduce it too. In the words of Rhea Myers, ‘the art world and capitalism in general loves nothing so much as that which it can’t buy’.[20]

Resale Rights and artistic agency in a local context

Widely lauded by supporters for its ability to deliver unprecedented agency to creators, one of the key developments enabled by blockchain technology is an early-career artist’s ability to implement Artist Resale Rights–a creator’s entitlement to a fraction of future sales–by encoding these rights into transaction conditions. For emerging artists without widespread name-recognition, the most salient threat to their IP is the risk that accompanies sharing original work online. Without recourse to inaccessible legal aid (the reach of which is severely limited in the online realm anyway), a number of local artists–both emerging and established–have expressed being stuck between a rock and a hard place; they’re wary of pervasive copyright infringement, yet feel that it’s essential to share their work online in this age.

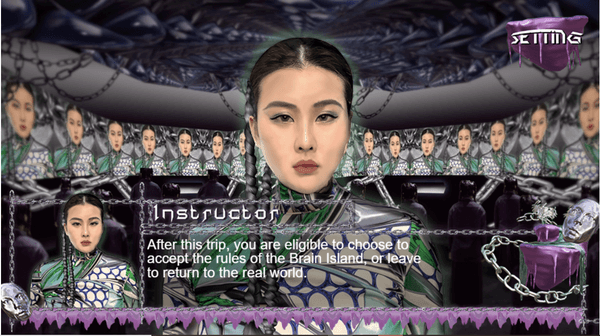

This shared sentiment is what prompted the project Free of Charge (freeofcharge.space), an online exhibition facilitated by artist-run space MEANWHILE and developed in 2020. Free of Charge sought to platform emerging digital artists, particularly those with a tendency to proliferate their work through social media. Two local artists were selected, Xi Li and George Turner, based on the creative labour evident in their intricate digital works; various technologies are employed across their combined practices, from Augmented Reality and photographic modelling to integrated video art. In comparison to the majority of digital art being uploaded to NFT marketplaces, Li and Turner’s works made a more effective statement about the level of conceptual engagement, labour, and sophisticated use of technology that abounds in social media circles without equitable financial recognition.[21]

The homepage of the exhibition had two calls to action: ‘enter with charge’ followed by the option to ‘enter free of charge’. Visitors who chose the former option could enter any value up to $100 via a Paypal plug-in, while those who selected the latter were directed straight to the artworks. The intention was to appropriate a common trend for downloading programming tools, used here to prompt consideration of visitor’s usual consumption of digital art for free, presenting instead a chance to evaluate how much the experience is worth. While we didn’t expect visitors to spend any notable amount to enter the site (and any proceeds were split evenly between the artists), the burden of choice was present–an alternative to the usual mode of likes and fire emojis to acknowledge serious artistic labour. Besides platforming early-career digital artists, the exhibition’s premise was to highlight the changing course for shared artistic experiences on the internet, given the rise of Patreon and blockchain applications. The possibility for artists like Li and Turner to protect and monetise their creations, without inhibiting their ability to share work with their immediate audiences, exists with NFTs, yet tellingly this isn’t an avenue that either Li or Turner have pursued.

Concluding thoughts

In keeping with the historically slow conversion of the local art scene to international trends, the reach of blockchain technology has only been felt here by a very small handful of individuals. Those with a vested interest in an artist’s proprietary rights–art dealers and auction houses, and artists participating in the traditional market–have barely engaged in the conversation, which for the most part remains speculative and hyperbolic as opposed to reality-altering. This isn’t necessarily a condemnation, rather an observation of the relevance that global shifts in art infrastructure has for local and early career artists. In March 2021, the Aotearoa creative industry commentator The Big Idea published an article echoing the uncritical rhetoric of international journalists, explaining how NFTs could change the game for independent creatives in Aotearoa.[22] Following this one-sided piece, another was swiftly published on the platform, this time addressing the technology’s flaws. The article began with this disclaimer: ‘We’ve received considerable–and considered–feedback from both sides of the NFT divide, and agree that it is pertinent to flesh out this debate.’ [23]

What this confirms is that there exists a notable amount of local interest as well as scepticism towards the technology, though interest is one thing and uptake another. While Aotearoa is yet to see artists create work about blockchain technology’s complexities or historic precedents, the aforementioned artists exploring NFTs seem to reflect a broader trend: those with a stake in alternative art markets are initially enthused by the possibilities blockchain can bring. This initial excitement tends to be followed by dejection as artists conduct more of their own research, or in some cases with the hope that NFTs’ problematics will be resolved if more diverse creators buy-in and influence its future direction. This latter narrative may have originated with marketplace developers seeking registration fees, but one thing is for sure: the artists who believe in this positive direction do so in earnest, and not without an understanding of the historic conditions that led to this moment. Perhaps it is a sign of how broken the current financial system is when individuals are willing to place their bets on a fraught notion of the future, inspired by the potential for change that blockchain still has to offer.

Nina Dyer is an emerging curator with a background in Art History and an interest in socially engaged and interdisciplinary practices. Dyer is the current Exhibition Curator and Manager at Depot Artspace, and has held positions at Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi and Enjoy Contemporary Art Space. In 2020 she curated Free of Charge, a digital exhibition facilitated by MEANWHILE gallery. Her writing has been published by Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Enjoy, and The Art Paper.

Footnotes:

[1] Viable energy-efficient blockchains exist which use Proof of Stake minting processes rather than the emission-heavy Proof of Work system employed by Ethereum (the currency which most NFT sales are tied to). Whether these alternatives are efficient enough to completely cancel out climate concerns depends on who you ask. Antsstyle, ‘Criticisms of blockchain consensus mechanisms in cryptocurrency usage (PoW, PoS, etc.), and why no major cryptocurrency has moved from PoW’, Medium, May 18, 2021, https://antsstyle.medium.com/explanation-of-blockchain-consensus-algorithms-pow-pos-etc-735fa50d93c8.

[2] Ruth Catlow, “Introduction,” in Artists Re:Thinking the blockchain, eds. Ruth Catlow, Marc Garrett, Nathan Jones & Sam Skinner (Liverpool: Torque Editions & Furtherfield, 2017), 34.

[3] Danny Butt, “Local Knowledge and New Media Theory” in The Aotearoa Digital Arts Reader, eds Stella Brennan and Su Ballard (Auckland: Aotearoa Digital Art and Clouds, 2008), 31 – 32.

[4] Artist Krista Kim, quoted by James Parkes, “Artist Krista Kim sells “first NFT digital house in the world” for over $500,00”, Dezeen, March 22, 2021, https://www.dezeen.com/2021/03/22/mars-house-krista-kim-nft-news/.

[5] The ability to authorise or “mint” a unique token is dispersed amongst other users of the respective chain in a self-regulating fashion.

[6] Internet Art, ed. Rachel Greene (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 75.

[7] Heath Bunting and Natalie Bookchin, ‘Criticism Curator Commodity Collector Disinformation’, accessed December 13, 2021, http://www.irational.org/heath/c4d/.

[8] Olia Lialina, “All You Need is Link”, Rhizome, February 21, 2017, https://rhizome.org/editorial/2017/feb/21/all-you-need-is-link/.

[9] Jasmine Liu, “New Study on NFTs Deflate the “Democratic” Potential for the Medium”, Hyperallergic, accessed December 6, 2021, https://hyperallergic.com/697239/new-study-on-nfts-deflates-the-democratic-potential-for-the-medium/.

[10] “Introducing Glorious”, Glorious, accessed November 29, 2021, https://www.glorious.digital/.

[11] Thomas Clark, Instagram conversation with the author, November 29, 2021.

[12] ‘Transmission: Kereama Taepa”, Objectspace, accessed November 29, 2021, https://www.objectspace.org.nz/exhibitions/transmission/.

[13] Motoko Kikkawa, email conversation with the author, September 26, 2021.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Max Mollison, Instagram conversation with the author, October 30, 2021.

[16] Evan Woodruffe, email conversation with the author, December 14, 2021.

[17] There has not yet been any case law to demonstrate whether Smart Contracts hold up to external legal scrutiny, which would seem to render them as little more than a good-faith social contract between users.

[18] Hito Steyerl, “If You Don’t Have Bread Eat Art!: Contemporary Art and Derivative Fascisms.”, e-flux, October, 2016, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/76/69732/if-you-don-t-have-bread-eat-art-contemporary-art-and-derivative-fascisms/.

[19] ‘Image anarchism’ is a term coined by artist and art-world troll Brad Troemel. The term describes in particular the behaviour epitomised by Tumblr users, the same platform that prompted Monegraph co-founder Kevin McKoy to research blockchain applications.

[20] Rhea Myers, “How OG Crypto Artist Rhea Mysers Sold a Never-Seen Artwork at Sotheby’s”, interview by Laura Shin, Unchained, September 21, 2021, audio, 15:26, https://unchainedpodcast.com/how-og-crypto-artist-rhea-myers-sold-a-never-seen-artwork-at-sothebys/.

[21] The works produced for this project exercised some of the utopian freedoms envisaged by early net artists–namely, producing experimental workwithout being bound to the physical limitations of a gallery space–while maintaining a critical approach to some of the more sinister aspects of digital culture.

[22] Ben Jardine, “Why Creatives Need to Know About NFTs”, March 18, 2021, https://www.thebigidea.nz/stories/why-creatives-need-to-know-about-nfts.

[23] Ben Jardine, “The Dark Side of NFTS”, The Big Idea, March 22, 2021, https://www.thebigidea.nz/stories/the-dark-side-of-nfts.

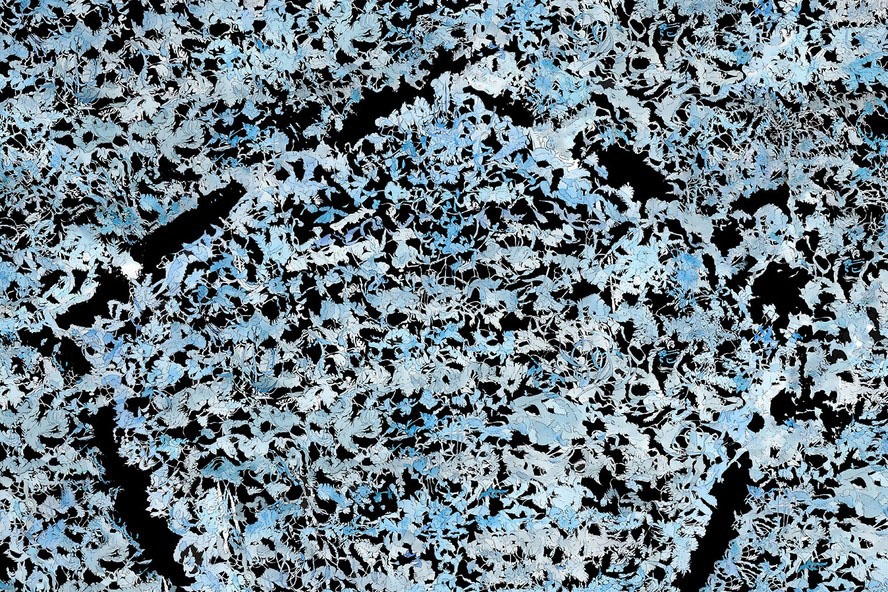

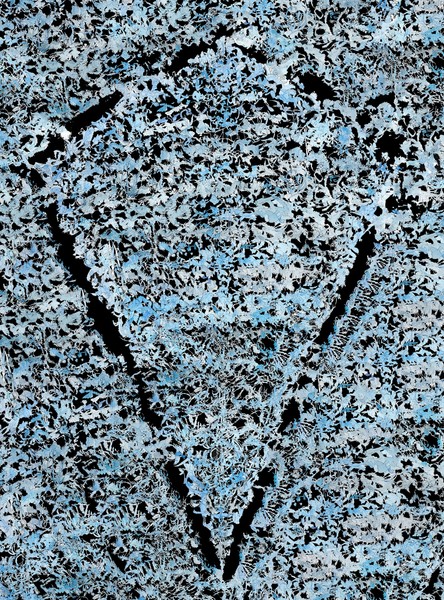

![Still from George Turner's cp001-010 [Injected]](/static/4167d7d6d74187ba4878270cbf533031/ff59c/George-Turner.png)