By Robert Leonard

A small image in Stella Brennan’s 2004 exhibition Tomorrow Never Knows gave me pause. Her digital print reproduced an aerial view of a gigantic geodesic dome on fire, a plume of dark toxic smoke billowing from its pre-fab acrylic panels. It could have been a riff on Ed Ruscha’s The Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Fire (1965-8), except that Brennan’s fantastic image was for real, a genuine news photo of Buckminster Fuller’s forward-looking US Pavilion for the 1967 Montreal World’s Fair, a “symbol of man and his world”. In 1976 a welding accident started the fire and all the acrylic cladding melted away in just half an hour, the mishap making geodesic domes a somewhat harder sell. Brennan chanced on the image flicking through the 1978 instalment of Shelter, the faddish “scrapbook of building ideas”, in its special section on dome building. To me Brennan’s purloined image conjured up those 1970s disaster movies obsessed with the hubris of Think Big projects and looked forward to Chernobyl, Bhopal and 9/11. Brennan reproduced the shot as a sepia duotone, but this styling was tongue-in-cheek, her aim being to puncture romanticism, curdle nostalgia.

Brennan maps modern times from a postmodern vantage point. Her work explores the history and currency of modernity, the dream of human perfectibility and emancipation premised on rationality, technology, progress. She researches modernity’s grand schemes and utopian ideologies, and their fate in the brave new world of the present. Her perspective is consciously generational. As she puts it: “Being 25 at the start of the 21st century has given me a fairly intensive experience of millennial preoccupation. I have looked on as my childhood dreams of Space and Armageddon turned into the Challenger disaster and UN Peacekeeping missions.” Born in 1974, Brennan missed the Paris riots and the Moon landing, events that would shape her world, and inherited feminism and greenie politics as givens. She did however witness the digital revolution first hand.

In her MFA dissertation, Brennan offers the night sky as a metaphor for history. She points out that the light from distant stars takes years to reach us. The Crab Supernova remnant is about 4,000 light years away, and the Andromeda Galaxy 2.3 million. We see them as they looked aeons ago. The stars themselves have long since moved on; some are dead. Astronomers are like archaeologists, they read the night sky as layered with historical traces. In doing so they realise that the stars’ appearance says as much about us, about the unique location in space-time from which we regard them. Brennan’s works emulate this condition, enfolding distinct moments, even distinct historical epochs, but always with an eye to the here and now. Take her 2001-2 stitch-per-pixel embroidery of her iMac OS 8 desktop. It took over a year to do, and she needed help; a sewing circle of friends and family helped complete it. And, by the time it was done, it was obsolete. Brennan had a new computer, running OS X. Translating the digital into the pre-industrial, Brennan’s work yokes opposing values – the computer screen’s currency, immateriality and speed with craft’s traditionalism, materiality and laboriousness; the ubiquity of the iMac, the quaintness of stitchery.

The woven computer screen can be read as daft, wrong, like an expressionist painting converted into paint-by-numbers. Perhaps the artist didn’t really understand computers, what was at stake in them, their revolutionary implication. It can also be read as deft when it prompts the consideration of more subtle historical connections. Brennan recalls the use of punch cards to programme automated Jacquard weaving looms during the industrial revolution, and Ada Lovelace’s proposal to use them to programme Charles Babbage’s analytical engine, the proto-computer. The piece suggests questions for feminists and Marxists. Was the auto-mation of traditional women’s work liberating or oppressive? Were women – are women – the winners or losers with industrialisation?

Brennan’s time-hungry work asks that the viewer take time to consider such things. Although the title – Tuesday 3 July 2001, 10:38am – suggests an instant, the piece enfolds time: the time taken to view the work, the time taken to make the work, and the whole stretch of technological, economic and social progress from the Bayeux Tapestry through the industrial revolution to the Macintosh. Brennan certainly puts an interesting spin on On Kawara.

Brennan relates the daft-to-deft flip to cargo cults. These religious and social movements developed when isolated Melanesians were suddenly confronted with the products of industrial modernity. Lacking the back-story of their function and evolution, they read Western commodities through their own values, making weird sense of them. Cargo cults show us not only the strange ways that outsiders can read our commodities, but also the peculiarity and contingency of our own understanding of them. They make us consider not only the gaps in their understanding, but also the assumptions and blind spots that underpin the naturalism of our own common sense.

Like cargo cultists, Brennan misreads. It takes a little while to work out what’s wrong with her video diptych ZenDV (2002). Brennan ran the digital blue screen and colour bars through a filter that emulates the scratched textures of celluloid film. Today’s moviemakers use this effect to imbue pristine digital images with authentic analogue texture, feeding our nostalgic desire for reassuring grain. And yet the irony of this work is that the blue screen and colour bars are the last things you would apply the effect to: they never had grain. Similarly, Brennan’s title promotes her videos as devotional objects when surely only a Martian or a bewildered head-hunter would make the mistake of meditating upon them. Like the embroidery, ZenDV enfolds time. It makes us ponder our evolution from analogue to digital, and the tricks we play on ourselves to soften the transition.

Brennan creates evocative mixed-up structures. For her 2001 installation The Fountain City, she walled off the space with polystyrene blocks. The wall was lit from within using fluorescent tubes, giving it an ethereal temple-glow. At one end, a head-sized gap allowed viewers to inspect the wall’s interior spaces, which suggested vaulted architectures both ancient and space age. The utopian title recalled the Emerald City of Oz; in fact it is Hamilton city’s official tourist moniker. Brennan added a soundtrack of downloaded waterfall samples so tragically compressed they actually sounded unnatural, more like white noise. At once primitive and futuristic, natural and artificial, secular and religious, The Fountain City defied interpretation. It suggested the tele-scoped histories that typify science-fiction, where mud huts have hydraulic doors, people ride personal hovercraft but wear bearskins and still believe in the divine right of kings. Science-fiction is deranged history, carnivalised history. Sometimes it serves to obliterate historical understanding – as if to make us believe that somewhere mud huts with hydraulic doors might be possible. Sometimes in offering an estranged vision of the present it sharpens our consciousness of history, alerting us to contradictions.

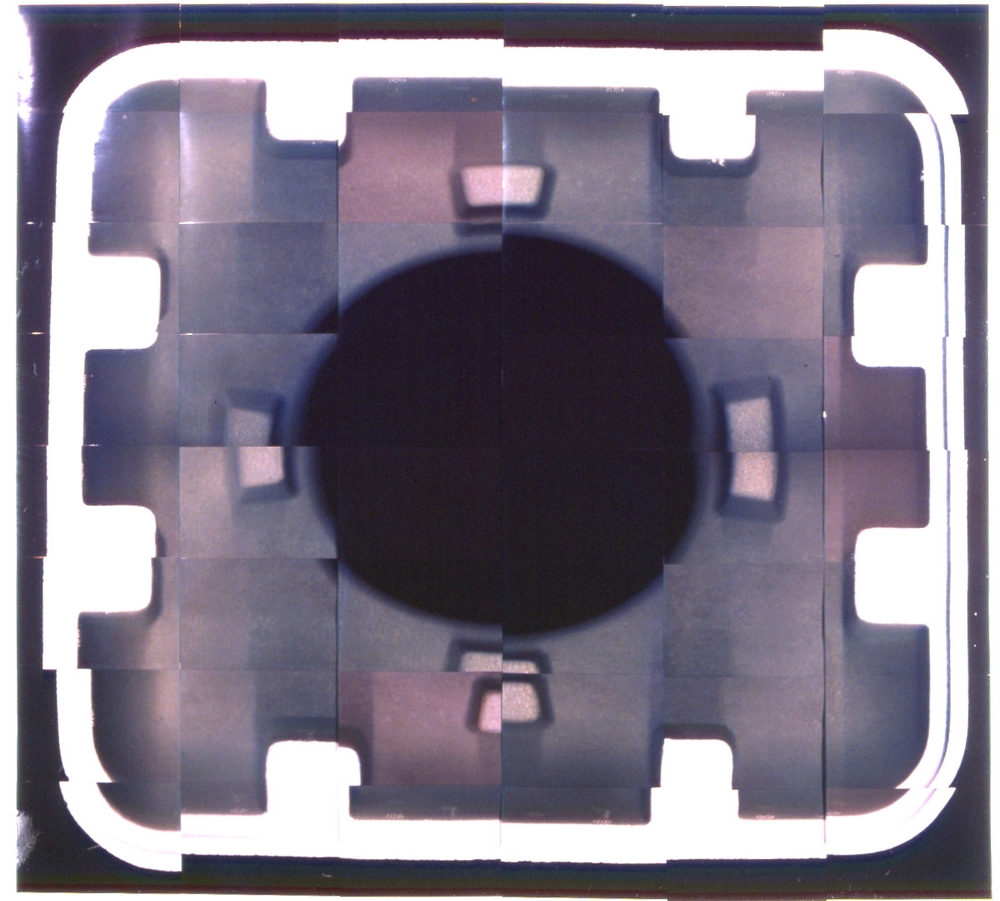

The cargo cult idea has relevance for another reason. We live in a world of technology so advanced that no one really understands it. Legend has it that only one person in the world knows the complete process of microchip assembly; others know bits of the process only. In many ways we are ourselves cargo cultists, recipients of advanced cultural material we can’t fathom. Brennan alludes to this in iBook Triptych (2002), where she monumentalises flatbed scans of the underside of her lovely new laptop – the latest – and the polystyrene packaging that came with it. She blew up the images as large as possible, tiling prints like she were Voyager photographing a distant planet, too big to capture in a single pass. However the lush information-rich images don’t tell us anything worth knowing about the computer. The polystyrene husks are irrelevant, and even the computer’s shell is just packaging of a kind. What is remarkable about computer technology isn’t visible to the eye. And perhaps that’s why computer design has to be so slick and fashionable, because we don’t register technology’s advance unless it comes in a new-fangled box with surprising new desktop gimmicks. Brennan succumbs to the culture’s general fetishisation of packaging, scrutinising it up close, like a dumb ape checking out the surface of the monolith in Kubrick’s 2001, with no idea how it works. The quasi-religious dimension of Brennan’s fascination is signalled by the altarpiece format.

Brennan’s oeuvre lacks stylistic consistency. One minute she’s using cheap polystyrene packaging to parody retro-moderne interior design, the next videotaping rustic salt-glazed pots as her computer mindlessly recites Hundertwasser’s “Mould Manifesto”. But however disparate the works are in appearance they are linked by a consistent methodology. Brennan’s sculptural language, if you can call it a language, is not expressive (it isn’t about saying something), it’s more experimental (it asks: what happens if I put this with that?). Locked on readymades, found objects, artefacts, her approach consists of presenting them, re-presenting them, arranging them, juxtaposing them, and translating or processing one through another. This approach has its basis in Marxist dialectics. The Marxist-modernist idea – that history involves a dynamic interplay of antagonistic forces that resolve into a higher synthesis – has long been influential on artists. Modernist artists have frequently brokered bad marriages between odd elements – images, styles and processes – to release contradictions or expose unexpected sympathies. The idea particularly inspired those 1960s radicals, the Situationists, whose favourite strategy was code-crashing, which they called detournement: deflecting, diverting, rerouting, distorting, misusing, misappropriating and hijacking chunks of dominant discourse to expose its ideological undercarriage. Brennan however prefers to see her dialectical practice less in terms of antagonism than ambivalence.

Brennan is not only an artist, she’s also a curator and writer. Not only do Brennan’s curatorial projects provide a useful entry point into her art, the very idea of curating does. Her art is essentially about artefacts, researching them, presenting them, reframing them. This was Brennan’s own point when, in the face of harsh opposition from Elam’s powers-that-be, she insisted on curating a group show rather than offering a solo exhibition as her final MFA submission. Nostalgia for the Future, at Artspace in 1999, explored the recuperation of passé modernist style as retro-chic.

Modernity is a culture of eternal newness but also one of eternal return. Things go out of fashion but come back; today’s rubbish is tomorrow’s antique. Walter Benjamin argued that commodities attain a strong critical force when they drop out of fashion, when they are abject and nasty, before being recuperated as “vintage”, before they become That 1970s Show. Brennan’s centrepiece, Guy Ngan’s techno-futuristic 1973 Mural for the Newton Post Office was a great example. It had been “permanently” installed in the Post Office beneath Artspace but, deemed unfashionable, it had been removed during a late 1980s revamp and dumped in the basement. Rescued for the show, the work opened up a forgotten vista of art (Ministry of Works modernism) and utopian social engineering (town planning). It surprised.

If the Ngan was an artefact that Brennan rescued, the other works, all recent, were actually or metaphorically rescued artefacts. Julian Dashper stretched garish old fabric to make a painting; Fiona Amundsen photographed our old motorway interchange, Spaghetti Junction; Mikala Dwyer’s work included a Danish designer lampshade from her childhood; Jim Speers’ lightbox looked like a deposed sign for the global systems-and-control company. Brennan presented two works of her own: a signature wall painting represented the groovy logo for Stella, a long defunct local electronics company; and Zen, a video of a DIY kinetic light sculpture (she made it from instructions in a hobbyist manual) back-projected onto an etched glass door, accompanied by a shrill electronic whine. There was a strong curatorial voice to the show and one almost had the sense that Brennan had effectively appropriated the other artists’ works as her own. The pieces she chose operated within her art’s existing concerns, syntax and rationale. Whether the show was Benjamin’s critical wake-up call or the advanced guard of recuperation was too close too call.

Brennan is hardly the first artist to develop such a research-based and curatorial approach to art making. Precursors and reference points would have to include England’s Independent Group, those pioneers of Pop Art, particularly Richard Hamilton’s 1955 ICA show Man, Machine and Motion and various members’ contributions to the Whitechapel’s 1956 exhibition This Is Tomorrow. Enamoured of new technologies, mass media, popular culture and other latest-things-in-latest-things, these Independent Group displays blurred any distinction between art and artefact, gallery and museum show. In the 1960s and 1970s there was also the research-based art-writing projects of Americans Dan Graham (reading a wider social context into minimalism) and Robert Smithson (with his trippy telescoped histories and sci-fi themes). Smithson’s essay “Entropy and the New Monuments” is one of Brennan’s touchstones. Also, in the late 1980s, Jewish-American artist Haim Steinbach presented commodities and other items on his Juddian signature shelves suggesting shop displays. His juxtaposed artefacts literally told time (clocks), moved in time (lava lamps and wave machines), and hailed from or referenced different epochs (antique Victorian money banks, contemporary latex vampire masks, rocks). Steinbach’s works folded time; they played with newness and nostalgia.

The most apposite point of comparison, however, may well be another New Zealand artist, a contemporary. Michael Stevenson’s recent social-history displays perversely align evidence – artefacts, documents, reconstructions and quotes – to provide stranger-than-fiction views of the recent past. For instance his project This is the Trekka at the 2003 Venice Biennale uncovered the story of New Zealand’s attempt to manufacture a New Zealand car in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Stevenson’s show drew on historical ironies. Although Cold War New Zealand aligned itself with America, it operated like a communist centralised command economy. While the quest to build Trekkas was informed by burgeoning nationalism and kiwi can-do, their guts actually came from Czechoslovakia; our national car was premised on behind-the-iron-curtain trade deals. Stevenson’s time-warped show looked like a reconstructed period trade display; its amateurishness and boosterism were tragic. This was neither how we remembered history, nor how we wanted to.

The comparison with Stevenson allows us to distinguish Brennan’s approach. Stevenson’s exhibition totally fulfilled Benjamin’s imperative, using forgotten, unfashionable, even repellent material from the recent past for critical leverage, to disorient the viewer and prise open history and rewrite it. It was a veritable “return of the repressed”. Stevenson wasn’t at all interested in recuperating the Trekka as cool. He’s totally sceptical about coolness, but Brennan isn’t. She is far more conflicted. Feeling seduced and abandoned by old modernist ideologies (and anticipating similar ecstasies and agonies at the hands of new ones), she identifies and prepares to criticise. The Benjamin in her holds out against the recuperation of the just past, but the rest of her is a sucker for it. Caught in a constant flip-flop, her achievement lies in being able to sustain and explore her ambivalence. She explains it more simply: “These things are really beautiful, but they are also quite troubling.”

Robert Leonard 2005